Painterly Woodcuts

Nikolai Astrup’s Woodcuts

By Kari Greve

The Norwegian woodcut pioneers: Edvard Munch and Nikolai Astrup

I do not know whether you are acquainted with ‘the modern art of woodblock printing’– ‘colour woodcuts’ and ‘black-and-white woodcuts’. It is an art form that interests me greatly. It comes originally from Japan, but is adopted in a somewhat different form here in Europe, one that is better suited to our art. Here in this country, Munch and I are two of the few who have tried our hand at this ‘modern woodcut’, as it is called in contrast to the previously known wood-engravings or what is also called: Xylography (almost a mechanical process). Munch is very enthused about my woodcuts and has previously bought 3 of my things.1

This passage from one of Astrup’s letters from around 1917 clearly shows that the artist was well aware of his role as a pioneer in woodcut art in Norway, as distinct from the process he refers to as ‘xylography’, which had become associated with reproductive wood-engraving for the purpose of book, newspaper and magazine illustration. Photomechanical advances in the second half of the nineteenth century further removed ‘xylography’ from original creative expression. The artistic revival of the woodcut began in the 1880s in Paris,2 where Edvard Munch (1863–1944) was inspired to make his first efforts in the autumn of 1896. He produced a string of masterpieces, which Astrup knew and admired. Astrup did not own any of Munch’s woodcuts, but the fact that the older and more famous artist appreciated and had actually bought three of Astrup’s prints obviously made him proud.3

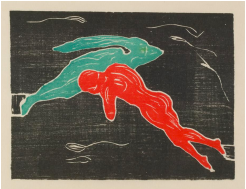

Neither Edvard Munch nor Nikolai Astrup had any formal training as printmakers, though the former benefited from professional expertise in Paris, Berlin and later Norway, where he also had a press for his own use. Astrup, working in Jølster, never had this degree of technical sophistication at his disposal. Both artists experimented freely and inventively with the woodcut technique. Edvard Munch devised a ‘jigsaw’ method for his colour woodcuts, sawing the carved block into pieces that could be inked separately and reassembled for printing. [fig. 1] Astrup applied oil paint to the blocks that were individually superimposed one upon the other to arrive at the final image, then added further colour by brush after he had completed the printing process. Although there is no evidence that these two Norwegian woodcut pioneers ever met or corresponded, they did have a mutual friend in Isabella Høst (1870–1937), who became Astrup’s unofficial agent for the sale of his woodcuts from 1911 to 1924. Isabella and her husband Sigurd (1866–1939) also knew Munch, who had returned to live in Kristiania in 1909, and it seems likely that Munch’s purchase of Astrup’s prints would have arisen from this connection.

Astrup’s woodcut technique

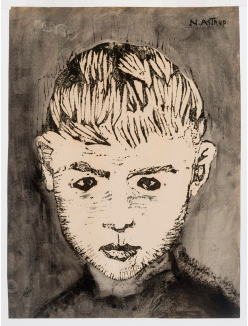

Astrup’s first woodcuts were made in the autumn of 1904, Small Self-portrait and Small Corn Sheaves, showing his early interest in both black and white and colour effects. His fascination with what he could achieve in black and white is evident in a series of portraits – bordering on caricatures – of figures from Jølster, as well as in subjects such as Head of a Boy, one of the three prints that Munch bought. Astrup experimented with black and white and chiaroscuro printmaking throughout his career, but his real interest lay with colour; apart from the Small Self-portrait, his first woodcuts are all in colour.

As material for his woodblocks Astrup preferred alder because the wood is soft and the grain is not very pronounced, but he also carved in pear and pinewood. He was solely responsible for the execution of every aspect of his woodcuts, with the aid of neither press nor professional printer, although he had some slight assistance in later life from one of his sons and the farmhands (see below). The prints were only ever produced in small numbers because of the labour-intensive and idiosyncratic nature of their manufacture, which Astrup recognised in a letter to Ingrid and Sigurd Høst of 1910:

In my own mind, they [the woodcuts] are too much like experiments. Nor have I really made use of the woodblock technique as it is usually employed by modern painters. I work in my own way, and several of my impressions can appear to be more paintings that woodcuts and this is, of course, really a fault – that is also why I have not considered exhibiting them. Some of them also require a lot of work to print, as I use 5–6 blocks for each impression.4

Four woodblocks for each colour print seems to have been the standard, but for the print Milling Weather six woodblocks exist. Astrup also used linoleum for some of his prints, for example one of the tone blocks for Growing Season at Sandalstrand.

Astrup applied colour to the woodblock as a painter to the canvas. He used regular oil paint, generally applying it with a brush,5 placing dabs of different colours on the same woodblock and occasionally painting in details directly on the block. He usually let each layer of colour dry before applying the next one, but he also experimented with printing a new layer before the first had dried, to achieve a softer effect of colour blending. He would dry his prints over the stove, observing how the colours changed as they dried, and would then match the next layer of colours to the ‘darkened’ dry ones. In a letter he recommended always keeping work for an extended period of time until sure that the colours had ‘settled’.6

Astrup printed in what he called ‘the Japanese manner’; that is, he placed the paper on top of the painted woodblock and transferred the colour by rubbing the back of the sheet using his hand, a cotton reel or a piece of wood covered with rags. The rubbing required considerable pressure, which on occasion caused small holes or tears in the paper. Keeping the precise overlap or registration between the different layers of colour was no easy task; many a time he would have to throw a piece of work away after the fifth or sixth block ‘ended up in the wrong place’.7

Astrup was very particular in his choice of papers. He ordered ‘Japanese paper’ (Kozo, a long-fibred, high-quality paper made from the paper mulberry tree) and Whatman paper (an English hand-made cotton paper) from his suppliers in Kristiania. They could not always provide him with what he wanted, particularly during the First World War when the Japanese paper was not available and he had to make do with paper of lower quality, which annoyed him.

A distinctive feature of Astrup’s woodcuts is the omnipresent added brushwork. He not only painted on his woodblocks, but he also painted on his finished prints. This was so prevalent that it can be used to distinguish Astrup’s own impressions from any made by others from the same blocks. He was his own harshest critic when regarding this practice: ‘… each “retouche” is unfortunate – as a single stroke with the paintbrush is enough to alter the mood of the picture, as it becomes a different style to that which is printed.’8 However, the painter in him never seems to have been able to refrain from adding some little extra dab of colour here and there.

Astrup was just as meticulous when mounting and framing his prints as he was with every other choice of materials. He started by cutting off the margins using scissors (and not always cutting very straight), then mounted the impressions on grey cardboard, which he was adamant about using, in order to bring out the colours in the prints.

Distribution of the woodcuts

Astrup never had a commercial gallery to promote and sell his prints. For their sale and distribution he mainly relied upon a network of friends and collectors who bought the work for themselves and helped sell his prints to others. A few of these helpers assumed the role of veritable sales agents. Isabella Høst played an especially key role in the distribution network. Her husband Sigurd, principal of the cathedral school in Kristiania (a position to which he moved from the equivalent school in Bergen), was a philologist, historian, art patron and altogether a central figure in Kristiania’s cultural life.9 Their home was a meeting place for a large circle of artistic friends, including the author Hans E. Kinck (1865–1926), whose lifelong friendship with Astrup began there, and Edvard Munch.

Astrup’s last solo painting exhibition, held in Kristiania in 1911, was the starting point for his collaboration with Isabella Høst. He would typically send her several impressions of a woodcut and ask her to choose for herself the one she wanted. She would then proceed to sell the remaining prints to people in her circle of acquaintances, sometimes also selling the one she had originally kept. Some of these clients became collectors, who would order particular subjects in specific moods and prescribed colours. Astrup went to great lengths to fulfill his clients’ wishes, even when he did not always share their preferences. His letters to Isabella Høst are full of discussions about individual prints and whether this or that client would be happy with them.

Isabella Høst did not have an easy task communicating orders and commissions between Astrup and her ever-expanding circle of clients. Astrup had a relatively chaotic attitude towards both price-setting and accounting: he would alternately blame her for selling the prints too cheaply and for charging too much. The end of their collaboration was brought about by the sale of the second impression of Foxgloves, when Astrup wrongly accused her of not having paid him for it.

Astrup’s close friend Per Kramer (1872–1946), who ran an engraving business in Bergen, also acted as a promoter of Astrup’s woodcuts, but lacking Isabella Høst’s many connections, he played a lesser role. Astrup expressed himself much more openly in his letters with Kramer, who would be given the task of sweet-talking clients when promised prints were not ready, or convincing demanding buyers to acquire a print: ‘you communicate better with him than I can – you find words for the mystique of a summer’s night and golden light etc.10

Nikolai Astrup’s woodcuts were already very popular in his lifetime and he received enough commissions to more than fill his working day. The income from the prints was probably the family’s bread-and-butter for many years: Astrup once wrote in a letter to Kramer that he was busy ‘printing banknotes’.11 The hard physical work involved was a big strain on his fragile health and weak lungs. He sought the help of his son Arnold and from farmhands and others to fulfill his commissions, but the perfectionist Astrup was rarely happy with his assistants’ work, so the help never really lightened his burden. He would frequently complain that the time spent on his woodcuts was taken from his ‘real work’, by which he meant his painting. However, just as often he contradicted himself and stressed the importance of the woodcut as an art form, as demonstrated by his decision to hold an exhibition devoted solely to the prints in Kristiania in 1918.

- Astrup to Hans Jacob Meyer, undated, most likely 1917, transcript in NB Oslo Ms. 402655:2.

- See Jacquelynn Baas and Richard S. Field, The Artistic revival of the Woodcut in France 1850–1900, Ann Arbor, MI 1984.

- Edvard Munch owned three black and white woodcuts by Astrup: Small Self-Portrait, Old Jølster Maiden and Boy’s Head. Wildhagen Gjessing 2010, p. 30.

- Astrup to Sigurd and Isabella Høst, 16 September 1910, NB Oslo Brevs. 531.

- For the black and white woodcuts he seems occasionally to have used a roller, primarily for economic reasons, as the brushwork used much more paint (Astrup to Per Kramer, March 1925, UB Bergen Ms. 1808 J3).

- Astrup to Per Kramer, undated, 1918, UB Bergen Ms. 1808 C1.

- Astrup to Sigurd and Isabella Høst, 18 June 1911, NB Oslo Brevs. 531.

- Astrup to Hans Jacob Meyer, 17 July 1920, transcript in NB Oslo Ms. 402655:2.

- Sigurd Høst supported the struggling artist Edvard Munch financially and played an active role in promoting his work, acting as a sales agent for Munch just as his wife did for Astrup.

- Letter to Per Kramer, 16 December 1924, UB Bergen Ms. 1808 J13.

- Letter to Per Kramer, December 1925, UB Bergen Ms. 1808 J7.

Fig. 1 Edvard Munch (1863-1944)

Encounter in Space

1898-9 Color woodcut on paper,

19 x 25.4 cm

The National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo

Fig. 2 Head of a boy

Black and white woodcut on paper,

27.5 x 17.5 cm

The National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo